Who is Christ for you?

Reverend Rebecca Newland

Lent 5A, 10 April 2011

Ezekiel 37.1-14, Ps 130, Romans 8.6-11, John 11.1-45

We are now just a week away from Holy Week and the events of Easter. This is the last Sunday of Lent. Next Sunday it is Palm Sunday when we enter into Jerusalem with Jesus and his followers. In today's Gospel Jesus takes that pivotal step towards the Holy City. Through Lent we have been alongside Jesus as he has encountered Nicodemus, the woman at the well, the man born blind and in today's' reading Martha, Mary, Lazarus and a whole crowd of grieving, questioning people. A question that Jesus has been answering is, "Who and what is he?"

In Mark, the earliest gospel written Jesus asks Peter and his disciples, "But who do you say that I am?" Dietrich Bonhoeffer called it the most important question the would—be follower of Jesus would ever be asked. Not what does the bible say. Not what does the preacher say. But who do you say Jesus is for you. So this is my question to each of us as we take these final steps to Holy Week. You have heard the stories. You have heard the sermons—today, who is Jesus for you?

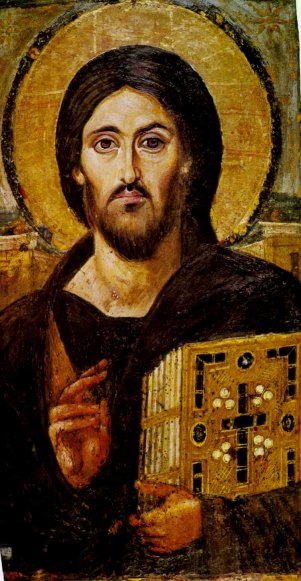

To help us reflect on this question I thought I would use the icon on the front of the Lenten booklet. As well as you having it in front of I am also going to put it up on the screen. You'll see why in a minute.

Icons are an ancient aide to worship and prayer. People do not pray to icons. They pray in the presence of them. St. John of Damascus wrote, "we are led by perceptible Icons to the contemplation of the divine and spiritual". The orthodox believe it is by keeping the memory of Christ and the saints before us through the Icons, that we are also inspired to imitate their holiness. St. Gregory of Nyssa spoke of how he could not pass an Icon of Abraham sacrificing Isaac "without tears"

This Icon was painted, or in Orthodox terminology, "written", in encaustic (a melted wax method) on panel in the sixth or seventh century. It survived the period of destruction of images during the Iconoclastic disputes that racked the Eastern church, in the 700s and 800s. It was preserved in the remote desert of the Sinai, in Saint Catherine's Monastery. During the thirteenth century it was coarsely over painted around the face and hands. It was only when the over painting was cleaned in 1962 that the ancient image was revealed to be a very high quality icon, probably produced in Constantinople.

Pantocrator is one of many names of God in Judaism. When the Hebrew Bible was translated into Greek as the Septuagint, Pantokrator was used both for YHWH the Lord of Hosts and for El Shaddai, God Almighty. The most common translation of Pantocrator is "Almighty" or "All-powerful". It means both all and strength.

Another, more literal translation is "Ruler of All" or, less literally, "Sustainer of the World". In this understanding, Pantokrator is a compound word formed from the Greek for "all" and the verb meaning "To accomplish something" or "to sustain something". This translation speaks more to God's actual power; i.e., God does everything (as opposed to God can do everything).

Christ Pantocrator is one of the most widely used religious images of Orthodox Christianity. It is the tradition of the Orthodox Church to depict "God is with us" by having a large Pantocrator icon inside of the central dome, or ceiling of the church.

There is something very special about this ancient icon. Each side is different.

The two different facial expressions on either side emphasize Christ's dual nature as fully God and fully human. But the icon also portrays Christ as the Righteous Judge and the Lover of Mankind, both at the same time. The Gospel is the book by which we are judged, and the blessing proclaims God's loving kindness toward us, showing us that he is giving us his forgiveness.

Having these two aspects of Jesus Christ is of course very biblical, particularly in John's gospel. John's Gospel begins with the declaration that the eternal Word became flesh, became human and then throughout the rest of the gospel these two parts of Christ are emphasized. In the story of Lazarus Jesus is so very human when he weeps over the death of Lazarus and the grief of his friends. Yet he also has the power to raise the dead. He brings Lazarus back to life.

There is a great cost in this action because it is the miracle that finally tips the religious authorities into a violent solution to this troublesome man of God. In this story John prefigures Jesus own death and resurrection and leads us into the events of Easter.

And this is a story about life and death. You remember we began Lent with the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and how their decisions and actions separated them from God? The story tells us that suffering and death became part of their world. Through greed, uncontrolled desire and wilfully rejecting God's way the relationship with God, creation and each other was fractured. Death and violence, revenge and retribution followed. That ancient story sets the scene for the story we are going to tell in Easter for it is through Christ's death and resurrection that the death that comes from our self-willed separation from God is defeated. When Jesus rises from the grave he brings in the place of condemnation and violence everlasting peace, abundant and fullness of life.

Who is Jesus for you?