Day 24 : Tuesday 21 March

Hear our voice, O Lord, according to your faithful love.

| Ezekiel 47.1-12 | Psalm 46.1-7 | John 5.1-16 |

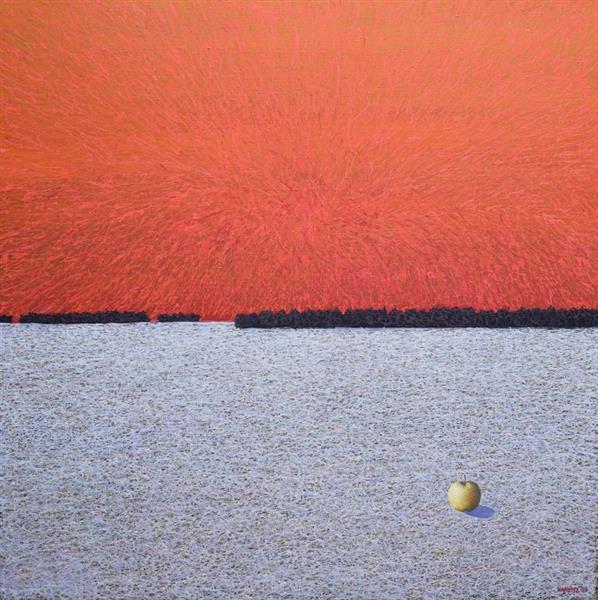

Ivan Marchuk, Silence all around, 2018

Morten Johannes Lauridsen. Nocturnes, III. Sure on this Shining Night (1994). Chamber Choir of Europe, cond by Nicol Matt.

Sure on this shining night

Of star made shadows round,

Kindness must watch for me

This side the ground.

The late year lies down the north.

All is healed, all is health.

High summer holds the earth.

Hearts all whole.

Sure on this shining night I weep for wonder wand'ring far alone

Of shadows on the stars.

— from James Agee. Permit Me Voyage. Yale University Press, 1934

Paul Bede Johnson “Why I believe in God. The Spectator. Christmas issue, 2012

My belief in God is not philosophical. It is not rooted in metaphysics or reason. It springs from the heart and the senses. It is practical. Every Sunday I attend the 11 o’clock Mass at the Jesuit church in Farm Street, Mayfair. I have been doing this, intermittently, for decades. For me, Farm Street is the centre of English Catholicism and brings back memories of my boyhood at Stonyhurst, the ancient Jesuit boarding school in Lancashire. The Mass is in Latin, and is sung to music written mainly in the baroque centuries. The sermons are brief and sinewy in the Jesuit manner. The congregation is a cross-section of Catholicism in England today, from old recusant families to Poles and Irish.

Among these people I feel at home, happy and safe. They share my view of life and what is likely to happen to us after death. After Mass we have coffee in the hall, and talk. They are not saints or martyrs. But they are good, charitable, above all thoughtful. We have a fellowship, we commune together. I imagine it was not so different, two millennia ago, among the early Christians in Rome. They recognised and greeted each other by making the sign of the cross. We still do so, and feel distinctive as a group. The first Christians were under constant threat, and faced the possibility of a horrific and public death. They drew strength from each other. We, unlike the embattled Christian communities in the Middle East and Africa, have no such fears. But we live in an alien world of pagans and materialists, who trumpet their ceaseless worship of hedonism in print and over the air, and whose deafening voices draw us together. We, too, reinforce each other’s faith. I feel nourished by spending an hour or so among my fellow Catholics, and a little more ready to move around the world of incomprehension and ridicule, even hostility, which surrounds us. Among the good people I meet in church, my faith flourishes, it raises its head proudly, I feel the sursum corda, the lifting of the heart which is the essence of the happiness Christianity brings.

So my first reason for faith is communal, and it is a very powerful reason. But even stronger is the assurance I get from prayer. I am not talking of public prayer, which is the essence and reinforcement of the communal spirit, but private prayer. This is an activity in which I engage every day, wherever I can. I try to follow the practice of the late Pope John Paul II, who when he was not actually obliged to do something else which occupied his mind, prayed. It is a habit I am acquiring, now I am well into my eighties and nearing the close of life. Prayer is the most remarkable — I am tempted to say sensational and spectacular — activity in which a human being can engage. For in prayer, however insignificant and lowly a creature we may be, we address privately but directly and intimately the most powerful creature in existence, the architect of the entire universe. Prayer, I believe — and this is what I practise — is a direct contact with God, which makes all the spine-tingling immensities of space completely irrelevant. We can talk to God, directly, secretly and whenever we wish, and on whatever topic which causes us concern. We can use whatever words or tone of voice we choose, but we do not need words at all, merely to articulate or just convey our thoughts. This ability to communicate with God is a reflection of the fact, and to me it is a fact, that in some indefinable but definite way we are created in his image, and thus can share our concerns with him. We know that he hears, registers and records, and that what we say in prayer has consequences, even though we do not, strictly speaking, conduct a dialogue with God, for we are more in the nature of petitioners than interlocutors. For God to speak to us is exceptional, though by no means unknown. There are many instances recorded by trustworthy persons, such as St Teresa of Avila and St John of the Cross.

All prayer is ultimately addressed to God but we pray to the saints and the departed faithful, and we pray for particular intentions and persons. At night, when I kneel by my bed, I pray for between 40 and 60 individuals, living and dead — family, friends, people I meet and feel sorry for or want to help, or who have asked for my prayers. Most of course get a mere mention, or I would never have done. A few get a separate, short prayer. This is a nightly ritual which I find satisfying, a relief and, in a curious way, enjoyable. It is part of the profound pleasure my religion affords. I also pray to named individuals, especially my patron saints, Paul and Bede, my father and mother and my elder sisters, all now (I trust) in heaven and listening. There are saints to pray to for particular purposes, like St Anthony of Padua, who finds things. And there are many departed souls, not necessarily Catholic or even Christian, whose sanctity I presume, and who can help. Thus, since I wrote a book on Socrates and came to admire him, he is a recipient of my prayers, and so are certain authors whom I have learned to love as my friends, especially Jane Austen and Dr Johnson.

(Continued on Day 25, tomorrow.)

May God our Redeemer show us compassion and love. Amen.